(January 2022) – By Jada Sirkin

*

Beyond the ideas of good and evil, there is a field. There we shall meet. When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to speak.

Rumi

I think in the entire documentary about the making of the Harry Potter saga there is not a moment where the people involved tell anything, shall we say, negative (challenging, complex) about the experience. My hypothesis is that the same level of idealization that we find within the fiction is operating outside of it, in the account of the making of the fiction. Thus, this documentary becomes another form of fiction. In any case, isn't every documentary, or rather every narrative, itself a fiction?

When Daniel Radcliffe (Harry Potter) says that, although he and his father could not talk, they would sit down to watch the saga and get excited together, Emma Watson (Hermione Granger) replies that the stories are a kind of refuge where we can go to feel safe when things are not going so well. On his part, Gary Oldman (Sirius Black) says that making the movies was like being with family (that idea is mentioned several times) and Helena Bonham Carter (Bellatrix Lestrange) says that the important thing about this story is that it gives us a sense of belonging, something everyone needs. The idea is that we all need to belong (to feel that we belong) and that's what stories are for —at least, this kind of story, which summons a kind of emotion that we can call archetypal. Archetypal information is ideal and therefore polarized information. An ideal is itself a polarization insofar as it functions as a structure (fixation) of inclusions and exclusions —the definition of good and bad.

The story of what the experience of making the films was like is perceived as idealized as the story of the fictional story of the world of the wizards; the behind-the-scenes narrative shares, with the on-scene narrative, the focus on cooperation, brotherhood, and family; togetherness is generated, most visibly in fiction, but also in reality, by the struggle against evil —the other. To idealize is to define and fix the division between the self and the other. Let us say that, if evil is equivalent to death in fiction, it is equivalent to failure —disorder— in real life. Making any film (let alone 7 films of this caliber) is something of an odyssey. By the end of the documentary, the leading trio says we did it: they went through the epic adventure (spread out over ten years) between the first and the last of the films, all that shared effort. On some level, filmmaking is also a battle against evil —let's say, against (not to say with) life, which, as we know, always messes up our plans.

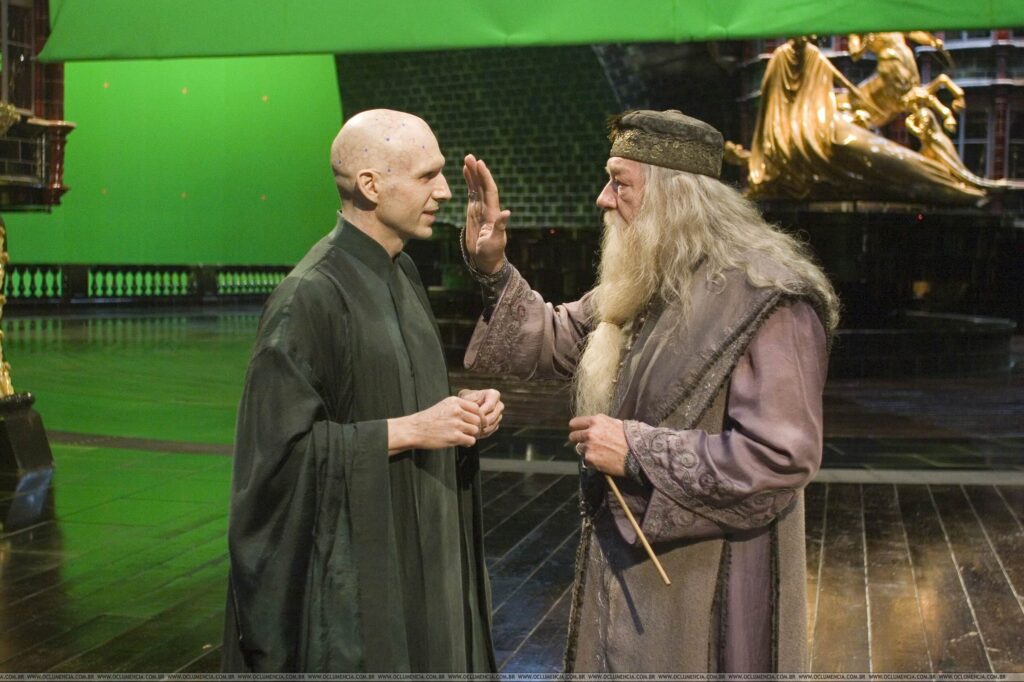

Whether we are talking about evil or the mess of life, we are talking about death: when death lurks, there is a cause that unites us: to defeat the darkness (the disorganization of the known, the familiar). Ralph Fiennes (Lord Voldemort) tells us that he enjoyed feeling powerful in the part of the villain. It's all about power. Ultimately, they say, it's all about the struggle of good versus evil. Of course, as in any archetypalized narrative, the poles are idealized —that is, defined and separated. Although it is suggested that Harry and Voldemort are two sides of the same coin, and although the story of the young wizard who was tempted by the shadow is told (although, I say, we know Voldemort's lost humanity), in the end it is, once again, about light destroying darkness. The monster, even if humanized by the tale of how he became a monster, is still just a monster —and therefore must be removed. Out of necessity, because the hero must be a hero —because heroism is the defense of our space of belonging: we need heroes to belong, to feel safe.

As we see in the behind-the-scenes narrative set-up of many productions, especially those from the north, the very act of shooting is understood as a heroic endeavor. No wonder the actors are deified: effort and dedication, hard work, generosity, companionship, family and fraternal values are highly appreciated. Gary becomes as much of a father figure to Daniel as Sirius is to Harry; we love seeing it, so we dedicate ourselves to narrating it. And to tell about it, we live it. It was beautiful to see Gary and Daniel together between takes, they say; and of course, it's beautiful, because we are beautiful and because we do the possible and the impossible to remember it.

In order to remember that we love each other, we build these kinds of experiences —we call it art, film, whatever. I'm not saying that the documentary exaggerated, or lied, although I am saying, clearly, that it did select; probably the experience of making the films was in fact that wonderful as they say, the question I ask myself is whether the need to idealize experiences leads us to create experiences that are close to the ideal. We live experiences because we know we will need to remember them. Money helps to create near-ideal contexts —myths, stories. Those of us who make very-low-budget films know that rushing and accumulating tasks on a single person, to give an example, are often very stressful moves. I can imagine that, being paid good money and having a trailer to retire to rest, the experience must be different —when the context generates a steady containment, talent is deployed with comfort and a sense of control. The cause is clear: a myth is being built. For that, it is necessary to control chance. The experience must be ideal. For it is around the ideal that we will meet —at least, that our idealized personalities will meet. In any case, however ideal it may be (seem), there are always difficult moments, tensions, difficulties, darkness that emerge in the inevitably complex game of collective creation: if this is so, why don't they tell us about it?

True, there are some moments, but aren't they also somewhat idealized? One is the moment when director Mike Newell breaks his ribs showing one of the Phelps (Weasley) brothers a move. The way the event is chronicled makes it more of an anecdote than a moment of emotional risk and relational learning. Granted, it's been years, and it makes sense that they now remember it as a purely fun moment. Yet... Another supposedly difficult moment is when they recount that Emma, overwhelmed by the fame thing (this fame thing finally hit home, she says) considered not acting in the later films. In the same way, the situation remains on an anecdotal level, covered and protected by the profusion of compliments and declarations of love between the participants. Everyone speaks highly of everyone else, everyone talks about how great the people they worked with are, and how incredible the experience was. Yes, okay, but isn't there something else? Isn't there a B-side? Where is Voldemort in all of this? Didn't anyone, at any point in the ten years of work, feel the slightest bit of contempt for anyone else? Wasn't there even the slightest bit of discussion?

For sure there was. The question is why don't they tell it. Why is it that what we can understand as the bad or the negative is so systematically excluded from the narrative of this creative odyssey? The moment when Emma and Rupert Grint (Ron Weasley) declare their love for each other, the moment when she herself and Tom Felton (Draco Malfoy) tell of how they became like brothers from day one, the moment when Jason Isaacs (Lucius Malfoy) tells of his admiration for Tom in the scene where Draco is forced to murder Dumbledore, I would say all of Robbie (Hagrid) Coltrane's moments in both reality and fiction, are moments that moved me, and that I consider beautiful; yes, but I wonder, isn't there something missing? Are we human beings that pure light? Is collective creation just a party of talented heroes? Where are the monstrosities of the creative process left? The darkness they try to banish in fiction for years, in the documentary (the fiction of fiction) is already banished. Is the good so separated and cut away from the too darkened evil?

Cutting out good and evil with such definition, putting a face and a name to darkness, allows us, once again, to push it into the distance, so that the need to assume darkness is blurred. Evil serves us to be the good guys. Having a monster with a body (no wonder why it takes Voldemort a while to get hold of one) allows us to stick the sword outside, gives us a north, a cause to fight for —we unite in the history of our collective causes. We humans band together, to a large extent, to fight for something. We invent enemies to feel a sense of belonging. The outside(what we must fight against, chance, disorder, otherness, death) is what justifies and enables the creation of the inside (family, siblings, community, the story of shelter and shelter as a story). In catastrophe films, the meteorite invites humanity to unite. When the meteor is subtle and mysterious like a virus, humanity, instead of uniting, confirms its ability to split and polarize. Voldemort is a clear enemy and when the enemy is clear we know what we have to do —there is no need to hesitate, the possibilities are life and death. If only the enemies were always so visible and defined; the thing, as we saw these past years, is way more complex.

Jean-Louis Comolli says: "Every film is a system, no doubt, but no humanly formed system presents itself without gaps, flaws, aporias, contradictions, without the staging of its own contestation or its destruction. It is the holes in the system that it is convenient to apprehend. (...) All the lights of the spectacle will not be able to put an end to the darkness of the world." Like the fiction of which it speaks, this documentary painstakingly selects the signs that weave the final luminous and spectacular (mythical) meaning. There is nothing that is not carefully included (therefore, also discarded) for the purpose of constructing that touching meaning. Justified by the context (a documentary that talks about the making of a series of fiction films), the bodies in front of the camera do nothing but talk about something else, refer to another moment; represent, in their memories, an experience of the past, clearly alive, as a physical account, in its present emotional vibration. We come together to remember —to construct memory: only a memory (a story) can be idealized. The present is never ideal. Remembering (idealizing) brings us together, and we come together to feel love —vitality. Myth is a highly exciting story; it takes us to an extreme emotional level where we cannot not feel united. We idealize (spectacularize) experience to feel belonging.

The telling of shared myths unites us in a common space of belonging. Although they are the leads, these bodies are primarily storytellers —narrative agents. The mission of the bodies (in this documentary that looks and functions as a fiction) is a narrative, representational mission. Even emotion seems to have a fictional neatness —modeled, orchestrated, well-lit. Nothing significant is lost, nothing insignificant has a chance to survive. Storytelling is a battle against insignificance. Says Comolli: "Filmed, it is not only my image that is at stake; it is my speaking image, my image as a speaking subject. What I say and what I don't say, the equation of my word and my body, that is what is filmed, what is problematic. The relation between said and unsaid is not directly measurable by the speaking subject. That is where it all resides. They escape, they do not "communicate", they err, they surpass themselves, they overflow. The unthought is revealed in the filmed word because that word is body, comes from it, is recovered in it." What does our body unconsciously express between the fibers of the narrative fabric? Can the most controlling narrative inhibit the emanations of the unconscious?

There is in the documentary only one moment (in my experience) when someone is speaking (I think it's Emma) and the camera takes Rupert in an ambiguous expressive movement that, for an instant, made me think he was bored, or didn't want to be there. How beautiful, I thought, what could be happening to him? For a brief period of time my imagination was able to detach itself from the path traced by the story, to associate, to create, to glimpse a complexity impossible to organize; but then I was taken over by the narrative speed, which left no gaps to the dangerous possibility of glimpsing other meanings. If we observe, almost the only silences left in these interviews are occupied by expressive movements that account for easily legible emotions. That is to say, those are not silences —because the bodies are saying something precise and clear. True silence is a space of ambiguity, it is a suspension of the communicative process: silence is a pause in the circulation of meaning, a dangerous moment because it can give rise to anything. Silence is the point from which everything is possible. If we speak of belonging, of family and of home, we have to say that the true refuge (let us say, the ultimate refuge) is not a story, as we/they like to say so much —the true refuge is silence. Is there not in silence something of the order of magic? Is not magic an expression of silence?

*

If the article was of interest to you, please share it and consider DONATING HERE so that we can continue our research. Thank you very much!