(September 2022) - By Jada Sirkin

*

1

The following notes emerge from RETICULAR films' research. Recently, at two screenings of the episode"The end" of our series TRAMA, I noticed that the conversation with the audience touched more on questions of content than questions of form. Again the divide between form and content? It is true that the invitation to both events already directed attention to what we can think of as the content of the fiction - we invited to a screening and a talk about the "themes": in this case the relational problem in the protagonist couple: the dynamics of cohabitation, the difficulty to recognize and communicate limits, fragility, etc. In the episode there is a scene in which a "secondary" character gets "distracted" and looks at some pictures of the Sahara desert that are pasted on the wall. After the second public screening of the episode, I asked myself: why doesn't anyone say anything about the photos of the Sahara? For me that moment has a curious, I would say poetic quality - I like to think that, secretly, that detail is as important as the situation of the main characters; that's why I'm surprised that no one comments on it. Of course, the episode has a well-defined main narrative line -what happens in the relationship of these two people-, and the moment of the photos is not linked to that main line -at least, not in an evident way. It is a moment of suspension, where the narrative seems to stop. I suppose it is normal for our attention to be directed to what we explicitly (narratively) consider "the important thing". I suppose it's normal for the not so "significant" details to be put on the background. Every now and then, however, someone does make a comment on, for example, the timing of scenes, the silences, the quality of the acting, the images (" such nice photography") - less narrative and more purely aesthetic issues. But it is not so common; what is more common is for our cinema to provoke conversation about human relationships rather than about the perceptual question, the "insignificant" details or the expressive sensibility of the actors. It is also true that there is a strong collective need, at least in certain "circles," to bring the conversation about how we relate to each other to the table; so it is natural that we use film as a trigger for that conversation we are needing to unfold.

2

Talking with Dama David and Sol Bordigoni about a new project we are developing, I realized the following: the exploration of RETICULAR films is not only a relational exploration; it is also, and above all, an aesthetic exploration. From what I have been reading and listening to (and, as I said, from what we ourselves have been projecting and stimulating, perhaps unconsciously), the RETICULAR project is usually associated more with the idea of a relational exploration (intimacy, human relationships, interpersonal communication, conversation) than with the idea of an aesthetic exploration. Still as if they were separate dimensions, it seems easier to focus on the themes than on the manners of our cinema. And I wonder if this is not a more general tendency, not only associated with our cinema: what is most often valued in a film is its story. Most of the podcasts or talks about cinema I've listened to are more about the themes of the narrative (the characters, the psychology, etc.) than about the vital vibration of the body in front of the camera - we pay more attention to the words than to the silence between the words; more to meaning than to sound; more to the mind than to the body. And, of course, what we do with cinema is equivalent to what we do with our lives: in our lives we also give more value to the situations (the stories, the meanings) than to the very fact of being alive (the sounding, the vibrating). Who pays attention to breathing when they are in the middle of an important conversation?

3

After recognizing that RETICULAR is not only a research of the relational problem, but also an aesthetic research, this idea popped up: relational exploration IS an aesthetic exploration, aesthetic exploration IS a relational exploration. When I wrote down the phrase, I didn't know what it meant; I still don't know, it came as an intuition, and at the moment of writing this line it still strikes me as a difficult idea to apprehend. I write to pull on the thread of intuition, I write to discover.

4

What can it mean to say that relational exploration and aesthetic exploration are equivalent? I wrote above that our cinema generates more conversation about human relationships than about the perceptual question. Is that so? I go back to pondering those comments that are sometimes made about images, film photography, etc., and this occurs to me: although at some level there is indeed attention paid to the aesthetic dimension, we still see that dimension as separate from the dimension of content and themes. As if the aesthetic had to do with the superficial -the image as surface- and the content was that deep message that we need to package in a form. As if there were a marked, hierarchical separation between the presentation of the subject (the how) and the subject itself (the what). Is there something in itself, detached from the way it is looked at? I think that this is the point, the difference we make between figure and background -what is on the background?, we ask ourselves, as if the truth were always there in the back. As if the figure were almost a necessary distraction. The problem lies in the distance -in the split we maintain between form and content.

5

The perceptual question (how we process reality, how we look, how we organize experience) is a question of sensitivity. That is what I mean when I use the word aesthetic. The word aesthetic has suffered a social trivialization - think of the culture of cosmetic surgery (aesthetic surgery in Spanish), which suggests that, to a large extent, we associate the aesthetic with "the superficial." If we go to etymology, we find that aisthesis has to do with sensitivity - if anesthesia is what puts us to sleep, aesthetics is what awakens us, what makes us more sensitive. So, the aesthetic problem is a problem of sensitivity. Now, isn't the way we relate to each other also a problem of sensitivity?

6

I also said above that it is easier to focus on the themes than on the manners of cinema - and of life. In music, the word theme (at least in Spanish) is used to speak of a melodic structure: the theme of a piece is a melodic motif, a sound sequence, a form. In music, the theme is not the content of the story (in our example, the difficulties in setting boundaries in intimate relationships), but part of the formal organization of the piece. With this, we can approach the notion that form and content are not separate dimensions. Theme is form, form is theme. When we glimpse that the situations of our lives respond to almost mathematical patterns, we discover that the content of the stories of our lives is also form. If we repeat ourselves (if, even with updates and variations, we humans re-live, over and over again, very similar situations), it is perhaps to recognize that pattern (mathematical, formal, musical) that underlies singular events. In astrology, the expression relational pattern is used to account for the choreographic figures that are reiterated, even if updated, in every interpersonal connection. The relational pattern, more than a content, expresses ( gives sound to) a form - rather, the notion of relational pattern demonstrates that the content is form: meaning is sound. When we experience situations that seem singular and unique to us, deep down we are actualizing structural patterns, essential choreographies.

7

The problem of form is the problem of sensitivity. According to how we perceive, so are the forms we see. Where does a form of life begin and end? What are the edges of the perceived object? That is decided by the subject - the intelligence that cuts itself out and looks. The possibilities of creative relational maneuvering depend on how we cut ourselves out, where we cut ourselves out, from where and for what we look - let's say, our relational possibilities depend on the development of our sensitivity. Where do you end and I begin? If we are terrified (as they say, in survival mode), the encounter with others will tend to the dynamics of attack and defense. Who pays attention to their breathing when they feel threatened? If we perceive ourselves as separate entities that must at all costs protect themselves from the other separate entities (who threaten with their difference), we are bound to fight. Fitzgerald wrote, "There is no trouble, only a silence with the sound of my own breathing." To fight is to not listen to the breath. Pascal said that all the problems of human beings stem from their inability to sit in silence doing nothing. Can we do nothing when we perceive (interpret) ourselves to be in danger? Can we meet each other without believing (so much) that the other puts us in danger? Better: what is the part of us that believes we are in danger when we encounter the other?

8

Conflict is a basic relational modality that arises from the need to survive. Conflict is the supposed impossibility of living with the tension generated by difference - it is not even the difficulty of accepting difference, but of accepting the inevitable tension generated by difference. Because we are very idealistic, and sometimes we pretend that the "acceptance of difference" is a "harmonious" process. Inevitably, difference generates tension. Tension is polarity, polarity is differential relationship. So the problem is not with the difference, but with the tension generated by the difference. Conflict is the dialogue that seeks to eliminate that tension - the dialogue that seeks to end itself. Conflict is still a form of dialogue (dialogue IS tension); conflict is still a possibility of encounter - but it is an encounter that seeks to define (who wins and who loses, who is right and who is wrong) in order to close itself. Conflict is often the most common mode of dialogue, both in our films and in our lives. Cinema reflects with obviousness the difficulty we have in listening, which is equivalent to the addiction we have to survive - terror. But this "we need to listen to each other more" is not a moral problem. If we make it into a moral problem, it is because we are not yet sensitive enough to simply listen to each other. Listening to each other is the simplest and at the same time the most complex thing in the world! Morality is both necessary and counterproductive - it prevents, but to do so it has to desensitize. Morality is like a painkiller. If we fence parks it is because we are not yet sensitive enough to regulate ourselves in our relationship with the grass, the trees and the statues, which, according to the governments, do not want to be painted with graffiti.

9

"What is most often valued about a film is its story," I wrote above. We recently recorded with Dama an episode of the podcast Out-of-orbit Fiction (cinema and astrology), and we talked about the series Transparent (2014, Joey Solloway). One of the questions we brought up had to do with this: the series, as the filmmakers tell it, came out of a need to put the issue of trans sensitivity on the table and thus make the world "a safer place." At the level of what we can call content, the series generates a strong movement and the social (macro-political) effect of its message of visibility and inclusion is unquestionable - for example, according to Solloway, many people decided to come out of the closet thanks to the series. There, art has a clear social value. What we mentioned in the podcast is that, in addition to what the series wanted and achieved, the aesthetic experience of watching that material can be many other things -sensitive micro-events. For example, with Dama we are moved by the people, the expressiveness of the actors' bodies, the singular grace of those human beings in front of the camera (beyond, or before, or thanks to whatever it is they are narrating). The power of Ali's character is also the power of the character/actress Gaby Hoffmann, the radiant, singular presence that does not depend on the narrative, but that the narrative contains and enables. The character of Sarah could not have been played by any actress other than Amy Landecker, with her unmatched micro-tonic subtlety.

There is something that no screenwriter could ever write. What I'm getting at is this: for me, Transparent is a great series beyond its subject matter. The political power of its proposal has to do not only with what we could call its message, but with the quality (the texture) of its scenes -let's say: its vitality. The expressive language of the actors is stunning, the dialogues have very complex and vibrant subtleties, the characters' attempt to listen to each other goes beyond queer and trans vindication: listening is not just a politically correct idea: the actors trained to enable a level of (physical) listening that goes far beyond the lines of dialogue that talk about the importance of listening to each other. Listening to each other is not only a problem for our minds; it is also, and above all, an adventure for our bodies.

10

Perhaps the idea is best understood by making use of the dangerous tool of comparison. Let's compare Transparent to Hollywood (Ian Brennan and Ryan Murphy, 2020), a miniseries that also touches on the theme of inclusion - in this case, of people marginalized by the heteronormative, white, patriarchal apparatus of the film industry. But here the theme is not so much music, but rather idea. Hollywood proposes a rewriting of history, presenting a fictionalized version of how classic Hollywood makes a telling inclusive turn - the gay African-American screenwriter, the African-American actress and the Asian actress win the Oscar: one of the great symbols of social recognition. The gesture is touching, yes, and appreciated, and even has its social significance; but there's a catch: what we might call the aesthetics (or style) of the series proposes a kind of processed experience that, rather than sensitizing, to me, numbs us. The bodies are perfect, the lighting is perfect, the dialogue is explanatory, the acting is highly coded, the choreography is seamless, everything is controlled, everything is meaningful. The message gets through, but at a high price. We get there (we get to cry), but at the sacrifice of a lot of vitality - it's the vitality we lose when we oversimplify the experience, when we eliminate ambiguity, when we reduce the volume (the shadow) of the characters, when we become didactic and underestimate the intelligence of the viewer, when in a conversation we focus so much on the content that we forget we have bodies, and that bodies breathe.

It's true that this is a spectacular comedy; funny and, even with all its simplification, it also has (inevitably) a lot of subtlety: it has subtlety, above all, because the actors' bodies never end up being able to adapt to the meaningful corset of the narrative. As much as the acting is forced to represent (to draw legible gestures) for the viewer to understand and cry (that's what it's all about: understanding and crying), still, the vitality of the cast cannot be eliminated-never. Patti LuPone is far more interesting than her character. Perhaps we overemphasize the character - we love you, Patti! One of the most wonderful things about Transparent is precisely the (aesthetic=political) decision not to romanticize the characters - neither for the good guys' side nor for the bad guys' side. Moura (Jeffrey Tambor), who does not become the protagonist (great intelligence-sensitivity here, in this decision not to focus on one character), is full of shadows, resentments, ambiguous looks that are not easy to read. With these two examples, we see how the same message, when expressed in different ways, is revealed as different messages.

11

When someone tells us something that happened to him, his account is only a part of the situation-of the encounter, of the exchange, of the scene. There are also the reasons (explicit or implicit) why that person tells us the story, there is also the heat that circulates between our bodies, and the language of gestures, what the unconscious unwittingly says, the textures of the table on which we rest our arms, the air that leaves one and enters the other, shared atoms, distractions, passing images, inexplicable resonances, life. There is also life. The whole weave (the complex) of phenomena makes up what we can call the aesthetic dimension of the encounter. The aesthetic dimension includes the narrative part (that small portion of the experience that the egos-narrators pretend to control), but the encounter is not only the unfolding of the reasons why we believe we meet. The aesthetic view is the one that takes on the mystery part. The scriptwriters cannot control the space between their words, or the tonal interval that the cast will choose between one vowel and another. It's good to have reasons to meet, but let's not think that we meet just for those reasons. Let's not meet just to say the lines of the script, let's not believe that we meet just "to talk". Let's challenge the idea that acting is only expressing what we understood to be happening to our characters.

12

Meeting each other is not just about going after what we believe we owe each other. To connect is not simply to use each other to confirm what we already know. Relating to each other would be to open ourselves to the otherness that the encounter with the other brings us - and the otherness does not come so much from the other as a separate entity, which brings us a bundle of differences, but from the encounter with the other. There is something that can only be set in motion in this singular and unique exchange. The other does not possess an otherness before encountering me. That otherness (that singularity, that different information that has the potential to open me up) becomes available to the extent that it encounters a system that, let us say, by destiny, summons it.

13

En Obra abierta Umberto Eco escribió que lo primero que dice una obra, lo dice por cómo está hecha. Jacques Rancière, en varios de sus libros, propone que una obra de ficción, más que contar una historia, lo que hace es proponer un orden de sensibilidad, una manera de ver el mundo, una forma de sentir y razonar. Jean-Luc Godard, hablando de su película El desprecio, sugería que toda película de ficción es, primero que nada, un documental sobre el cuerpo de lxs actores. Caveh Zahedi escribió que lo que necesitamos no son nuevas historias, sino nuevos modos de ver. ¿Sería lo mismo decir que, más que nuevos contenidos, necesitamos nuevas formas? ¿Tal vez nuevas formas de relacionarnos con esos viejos contenidos? Al parecer, Hitchcock primero se obsesionaba con imágenes y después buscaba historias que le funcionaban como contexto (o excusa) para poder usar esas imágenes. De su película Los pájaros (1963), lo que más me atrajo siempre es el silencio, los desplazamientos, el sonido de los tacos de Tippi Hedren. (Para más sobre Los pájaros, leer Los pájaros: historia Vs textura)

Con ánimo de amar (2000, Wong Kar-Wai) es una película que nos fuerza a reconocer que forma y contenido son lo mismo; pero es sólo un ejemplo extremo, en que el trabajo formal se impone como tema: los protagonistas, traicionados, representan a sus respectivos traidores, como si así, como si actuando de ellos, pudieran procesar todo ese dolor. En esta película, el trabajo de la cámara, la música, el color, la velocidad, la actuación, el diálogo y la narración están entrelazados a tal punto que el sólo nombrarlos como dimensiones separadas suena forzado. Esa historia no podría haber sido contada de otra manera; pero, en el fondo, ninguna historia puede ser contada “de otra manera” —porque la manera ES la historia. (Para más sobre Con ánimo de amar, escuchar el episodio 7 del podcast El espectador inquieto.)

In Mutual appreciation (2005, Andrew Bujalski), it is clear how the manner (the aesthetic decision) defines the story (the characters' relationship problem). A threesome, another situation of proto-infidelity, the cliché theme of jealousy - here, that old drama of betrayal unfolds with a singular and revolutionary aesthetic (political) intelligence: upon learning what happened between his girlfriend and his friend, Lawrence (played by the director himself) reacts in an ambiguous way - the direction does not force the actor to define an emotional line; and so, the actor allows different emotional textures to intersect in his body: the narration does not underline, the actor vibrates. What happens to Lawrence? We cannot manage to define him. That indefinition (that indeterminacy, that unsentimentality, that permission for ambivalence) gives us a key to understand why the problem of relationship is an aesthetic question. Mutual appreciation updates the theme of jealousy, infidelity and betrayal, taking that old dramatic structure to a level of great subtlety. The subtlety derives from the decision not to underline - not to define. It is an aesthetic decision that allows these bodies to represent that old scene without being trapped in the archetypal groove. (To go deeper in this film, read "Why MUTUAL APPRECIATION is an important film?"

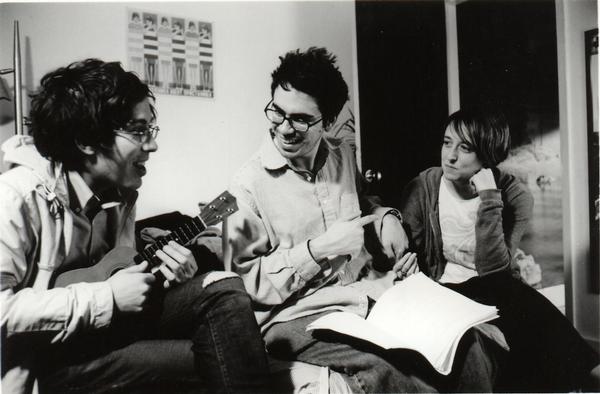

in MUTUAL APPRECIATION (2005, Bujalski)

14

We place a lot of value on the lyrics of songs, but songs are not only their lyrics. With music it becomes obvious: when we sing, we accept that the lyrics are not the most important thing. It's not that the lyrics have no value, it's just that they are not the most important thing. It seems that we need to say things to sing; rather than singing to say things, perhaps we say things to sing. As if we needed excuses to meet each other. We sing to acknowledge that we were already singing; and we dance to acknowledge that we can't not dance-the most automated movement of our daily lives is still a little dance. That is what the art of fiction reminds us: life is a dissimulated musical; sound IS meaning. Aesthetics would be the politics of the sensitive.

15

In synthesis, relating to each other and becoming more sensitive are the same thing. Becoming sensitive is to complexify our ways of responding to life situations - if the Hollywood mode is the simplified and archetypal way of reacting, in what other ways can we live and film? In what other ways can we relate to each other? The relational exploration is an aesthetic problem because relating to each other is to dynamize the unfolding of our sensitivity. Aesthetic exploration is a relational investigation because to become more sensitive implies, inevitably, to open ourselves to the different -above all, to open ourselves to inhabit the inevitable tension generated by difference. It is not usually a comfortable process, it is not a social party - it is, rather, a dislocated, mysterious celebration.

*

If the article was of interest to you, please share it and consider DONATING HERE so that we can continue our research. Thank you very much!